Beware words like - 'mysterious', 'real record', or 'hidden truth'.

Anunnaki, Nibiru and Nefilim gods are also a give away.

Be wary of the word Sumeria instead of the correct term - Sumer. I am also not a fan of the use of an adjective as collective noun - 'the Ancients'. But that may be me.

Flamboyant use of reception graphics/AI. Most with no connection to Sumer.

|

| King List... dammit!...... Lore Library, Youtube 02.08.24. |

- The Sumerian King List does not record the Anunna (Anunnaki). Gods are absent from the SKL.

- The Sumerian King List does NOT say that Earth was ruled by human-like gods.

|

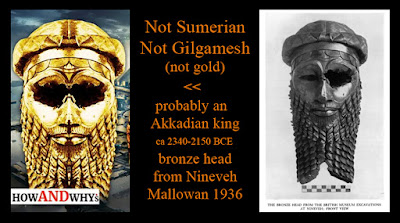

| Nothing in this image is Sumerian or relates to the SKL. Reddit 25.07.24. |

- The Sumerian King List does not say Gilgamesh was 2/3 god, nor that his mum is a goddess, instead his dad is described as a lilla spirit (a ghost).

And both pseudoscientists appear to use the same sources to achieve this aim, but with differing results, due to them each cherry-picking the numbers that they found most suitable to their narrative.

Berossus (via Eusebius) named 10 ancient kings who reigned Babylon before the flood for 120 ‘sari’. A Mesopotamian sar was 3,600 years, so according to this model the earliest kings reigned 432,000 years.

|

| 10 kings ruled ancient Sumer for 432.000 years? |

Erich von Däniken, on the other hand, again argued for ancient astronaut gods having artificially laid the foundation of human civilisation on Earth, but with fewer Anunnaki and much more selective cross breeding of alien gods with homo sapiens over thousands of years.

Unlike Sitchin he chose to use the numbers from a tablet in the Ashmolean museum, Weld Blundell (WB) 62, which also names 10 pre-flood Mesopotamian kings, but these king's have much longer reigns, adding up to 456,000 years. For some reason he did not feel the need to explain why these Sumerian kings lived for thousands of years (Däniken 1969, 25, 55).

It ought to go without saying that 1923 is over 100 years ago, and Assyriology has moved on since then. In particular, it has moved on from Langdon's style of argumentation, and from his translations. In fact Assyriology had already moved on 60 years ago (see Finkelstein 1963).

The SKL: What is it?

The Sumerian King List is a group of about 26-28 clay tablets that are inscribed in cuneiform with a list of kings of ancient Mesopotamia spanning from mythical time through to whichever ruling dynasty commissioned them (Gabriel 2018, 2021, Sallaberger & Schrakamp 2015, Marchesi 2010).

These tablets have been discovered during excavations at Nippur, Susa, Ur, Tells Leilan and Harmal, Isin and Kish. There are also a few tablets with no archaeological provenience. They have been studied since the early 20th century, and every now and then a new one has been found, so the number has almost doubled since early translations were done (Jacobsen 1939, Langdon 1923).

If an article claims there are 16 tablets they are relying on the list from Jacobsen 1939. The number was expanded to 22 by 1984 (Edzard 1984) and has now increased further to around 26, depending on criteria of inclusion (Gabriel 2018 lists 24, later 26 in 2021, but their list omits a few earlier inclusions, like WB 62).

The content of these tablets is inconsistent, names are changed or spelled differently, years of reign don't match, kings and whole dynasties may be missing or rearranged. The most glaring omission would be the complete absence of the dynasties of Umma and Lagash.

If you have even a passing knowledge of Mesopotamian history you may be shocked to discover that the SKL therefore omits famous historical kings like Gudea, Eannatum and Ur-Nanshe.

|

| The Scheil SKL tablet, listing early Babylonian kings. |

However, the focus of these tablets is on 'Kingship' as a divine power that is solely allotted by the gods, so the point of these documents is not historical reality.

The most complete copy of the Sumerian King List is on the Weld Blundell prism and translations of this version are the most widely cited. Academic translations may use this tablet as a form of master copy, that is combined with other tablets to create a complete text.

But because no two tablets contain the same information, all translations are an artificial restoration (Gabriel 2021).

Is a 4 sided clay prism in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (AN1923.444) that has no excavation history ('provenience') and may have been found at Larsa in Iraq in the early 20th century. It was donated to the museum by H. Weld Blundell in 1923.

The

prism was written in Sumerian cuneiform for an Old Babylonian dynasty, and

was commissioned at the end or immediately after the reign of king

Sin-magir of Isin (ca 1820-1800 BCE). We know this because he is the last king named.

In Eridug, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28800 years.

Alaljar ruled for 36000 years.

Then Eridug fell and the kingship was taken to Bad-tibira.

In Bad-tibira, En-men-lu-ana ruled for 43200 years.

En-men-gal-ana ruled for 28800 years.

|

| What is wrong with this picture?... History, Youtube. |

... abandoned Eridu(?)

...

One king reigned for 21,000 (/21,000+ ...?) years.

However, the earliest King List does not begin with the pre-flood kings, nor does it mention a flood.

Instead, it begins with kingship handed down from heaven to the city of Kish, and it only partially matches the later versions of the SKL for before the Akkadian kings.

In fact, in the light of this and other stylistic concerns, academic consensus considers that the pre-flood kings and flood section of the Sumerian King List were a later Babylonian addition to the original King List (Jacobsen 1939, Kraus 1952, Finkelstein 1963, Steinkeller 2003, Marchesi 2010, Sallaberger & Schrakamp 2015).

Awkward.

|

| Pre-flood kings, Old Babylonian tablet. © Schøyen Collection. |

The King List is arguably not Sumerian

To

add insult to injury, the name is somewhat of a misnomer.

The original Sumerian name of the text is nam-lugal - ‘Kingship’. It may also be called The Chronicle of

the One Monarchy in earlier modern literature.

But in fact, 'Sumerian' is misleading, as nearly all SKL tablets were written in the Old Babylonian period (2000-1595 BCE).

Only the one King List is earlier (USKL above). This tablet is now considered to be copied from an earlier Akkadian source (2340-2150 BCE), or from earlier sources that had copied an original Akkadian document (Steinkeller 2003).

Because these tablets were produced over hundreds of years and for different dynasties the tablets differ in content and usually end with the dynasty that commissioned them. Equally, the lists were copied by scribes over a long time, so there are errors.

|

| Sumerian cuneiform tablet naming king Eannatum of Lagash. |

There is no Sumerian version of the King List (Early Dynastic, 2900-2340 BCE), and it ought to be emphasised that the Sumerians only left us complex recording systems from the second half of this period. Before the Early Dynastic cuneiform writing was a work in progress.

To sum up: there is only one version of the SKL from the very end of the 3rd millennium, the rest of the tablets are 2nd millennium.

|

| Sumerian Early Dynastic plaques naming kings Enannatum and Ur-Nanshe of Lagash. |

Sumer ≠ Mesopotamia

Sumerian cuneiform survived for writing religious and royal literature for nearly 2000 years after Sumer as a culture had been swallowed up by Akkadian and the language was no longer spoken in Mesopotamia (after about 2000 BCE).

In the same way that Latin outlasted Rome as the language of religion and power in Europe.

A cuneiform text written in Sumerian during the Akkadian or Old Babylonian periods is not actually a Sumerian text. However, the problem for clarity is that it is still correctly called Sumerian, because it is written in Sumerian.

|

| The casual conflation of Assyrian and Sumerian art does my head in. |

Although why ‘Sumer’ is considered cooler and more authentic than these cultures is entirely beyond me.

How reliable is the Sumerian King List as an historical document?

When these tablets were first studied in the early 20th century the historical accuracy was taken at face value and, like Manetho for Egypt, used as a baseline for creating chronologies by scholars.

Nonetheless, the extraordinarily long reigns of the earlier kings were always considered to be mythical, aided by the fact that a few kings are gods or mythical heroes, like Dumuzi, Etana, Gilgamesh and Lugalbanda.

And it didn’t take long for scholars to begin finding inconsistencies, because

the defining feature of academia is that it continuously builds upon

and adjusts its knowledge base.

Therefore, doubts were already being raised by the 1930s.

In the past 60 years the historical reliability of the SKL has been repeatedly challenged with experts now considering the hypothetical original should be dated among kings of the Akkadian period. And that this text was created with the purpose of legitimising Akkadian rule by the Sargonic kings.

Sargon of Akkad unified Mesopotamia and conquered Sumer ca. 2324 BCE.

Because of this and other concerns, the SKL is considered to be mythological for the kings who are listed before the ‘kings of Agade’ (Akkad). And as support for this most pre-Akkadian kings have mythically long periods of rule, whereas Sargonic and post-Akkadian kings have sensible length reigns that can often be confirmed by other historical sources.

Basically, Assyriologists now believe the Sumerian King List was created as propaganda to make the Akkadian kings look like they had cool (and legitimate) origins, a hobby that many ancient Near Eastern kings dabbled in (Edzard 1984, Michalowski 1983, Marchesi 2010. Sallaberger & Schrakamp 2015).

The same motive applies to the Old Babylonian versions of the text, with the added embellishment of even older historical connections, by adding ancient pre-flood kings who ruled Mesopotamia for thousands of years.

The extraordinary lengths of reign for these primeval kings are naturally to be taken with a pinch of salt. This is another classic literary device intended to justify a later king’s VERY ancient right to wear a special hat and invade other city-states.

Where does that leave us?

Well firstly, it leaves us with a lot of misinformation built from reinterpeting an ancient propaganda text.

From this shaky start more misinfomation is constructed by relying on the theories of a late 20th century pseudoscientists, like Erich von Däniken and Zecharia Sitchin, who both cherry picked out of date research to argue that astronaut gods colonised Earth.

It means Kingship was given to a city and its king, and it is worth noting that kingship was usually granted to humankind by either Enlil (who decreed fate) or by An (the sky/heaven god).

No spaceships, just supreme gods doing what gods do.

Conclusion

To sum up: The Sumerian King List as we know it is not an accurate historical document for the Sumerian period, nor to be purist, is it Sumerian. It is at best a later propaganda text that attempts to hang on the coattails of Sumerian royal coolness.

In addition, the introductory list of primeval kings ending with a great flood has been considered to be an Old Babylonian insertion since the mid 20th century. It is not original to the text and appears to have been added by Babylonian kings to beef up their claims of right to rule.

Finally, and somewhat obviously, none of the versions of the Sumerian King List mentions biblical Nefilim, Anunnaki, secrets of immortality, spaceships or aliens of any species. These claims are fraudulent speculation largely designed to generate profit for unscrupulous individuals.

I hope you learned something new, I know I certainly did.

Andrea Sinclair

August 2024

|

| Irrelevant AI graphics - Eat the Fruit Inc - Facebook 26.08.24 |

Don't just trust me, read some of these

Web links

ETCSL: Sumerian King List English/Sumerian text at Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature - https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr211.htm -

Sources and Further Reading

Gabriel, G. 2021. 'The "Prehistory" of the Sumerian King List and its Narrative Residue.' In The Shape of Stories: Narrative Structures in Cuneiform Literature, G. Konstantopoulos & S. Helle eds., 234-57. Brill.

Mallowan, MEL. 1936. 'The Bronze Head of the Akkadian Period from Nineveh.' Iraq 3(1): 104-110.

Steinkeller, P. 2003. 'An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List.' In Sonderdruck aus Literatur, Politik, und Recht in Mesopotamien, W. Sallaberger, K. Volk & A. Zgoll, 267-91. Harrassowitz.