|

| Detail of the Nineveh planisphere, King 1912, pl. 10 |

My blog posts are usually an organic process to write.

A not so subtle blend of exposure to online media, my level of irritation and how easy it is to access the information required to debunk a factoid. Sometimes they are fuelled by pure spleen, but once in a while they are also stimulated by an academic messaging me and saying -

'Hey, have you seen this bullshit'.

Today's post is the outcome of the latter with a healthy dose of spleen.

On top of which I was misled by the assumption that while the clickbait memes were bullshit, the original claim might have had some merit, and was simply misrepresented in the media.

This viewpoint changed drastically after I acquired a copy of the book in question:

A Sumerian Observation of the Köfels' Impact Event: A Monograph

By Alan Bond and Mark Hempsell (2008).

Self-published with WritersPrintShop as Alcuin Academics.

However, neither author is qualified to pontificate on the topic of ancient Mesopotamia, and the book is in fact a perfect example of flawed research done with the intention of promoting a theory that has no evidence to support it.

If anything, there is an over-abundance of negative evidence. In fact, this book represents a discrete selection of pseudoscience methodologies in relation to ancient Mesopotamia, no line skirting, or subtlety at all.

Bond and Hempsell argued that the cuneiform on the Nineveh planisphere documents an Aten asteroid strike that caused a massive landslide in Tyrol, Austria, at 1.23 am on the 29th of June 3123 BCE (Julian calendar).

Because even a basic understanding of geography may raise an eyebrow it should be added that they argue a Sumerian astronomer at Kish (in Iraq) saw the asteroid trail as it approached and later the impact plume, and this person meticulously documented the event.

Then this document was supposedly kept and copied for another 2473 years in the archives of various Mesopotamian cultures, incidentally changing from Sumerian to Akkadian in this process. Ending up on the Neo-Assyrian planisphere from Nineveh.

The astonishing survival of this document is explained by the event having acquired religious significance, serving as the basis for catastrophic myths in Mesopotamia and in other cultures. As their example they cite it as the source of the myth of the god Enlil supplanting the god Anu as supreme god in the creation.

Their book was immediately the object of criticism from academics representing a variety of disciplines on the basis of faulty reasoning, lack of evidence and errors in the data. And this situation has not changed in the 15 years since the book was published.

So why is this trope still hanging around, and where are the problems with it?

The first question is easy to answer:

It is not still around within academia, flawed science does not make a ripple there, but the book is nonetheless still published and available to purchase. In addition, the story itself has all the hallmarks of good clickbait, where words like mysterious, controversial, star map and Sumerians can be mix-and-matched with ease.

The Köfels event

Their date of 3123 is wrong

That is a super big error in the date of this event, it is also a few thousand years before the Sumerians developed complex urban society in southern Mesopotamia and about 4000 years before the development of written records of any kind in the entire Near East.

Nicolussi et al 2015, ‘Precise Radiocarbon Dating of the Giant Köfels Landslide (Eastern Alps, Austria),’ Geomorphology 243: 87-91.

|

| MysteriesrUnsolved, Aug. 2023 |

There is no evidence of an asteroid “impact” at Köfels

Both proposals have since been rejected in academia in favour of terrestrial causes, due to extensive further research resulting in a better understanding of geological conditions and the glaring absence of any form of impact crater from an asteroid.

Also, it turns out that the landslide was not one event, we now know it was a sequence of landslides over a period of time.

Hermanns et al 2006, ‘Examples of Multiple Rock-Slope Collapses from Köfels (Ötz valley, Austria) and Western Norway.’ Engineering Geology 83(1-3): 94-108.

Their date for Sumerian astronomy is wrong

Written language begins everywhere with the stuff necessary for organising large groups of people.

Therefore, there are no documents recording narrative events from this time, not scientific nor mythological, and there is currently no evidence they existed. Complex writing and recording took at least about another 300-500 years to be fully developed in Sumer.

The authors rationalise this tricky problem by suggesting two alternatives:

2) That the existence of no evidence does not mean that evidence never existed.

This is classic pseudo bullshit.

No evidence is no foundation for a sound argument.

It isn’t until the Old Babylonian period, in the early 2nd millennium, that evidence of documentation of celestial phenomena appears, e.g. the earliest record of the movement of a planet is from the 17th century (Venus) (Koch-Westenholz 1995, Ossendrijver 2013).

Instead most early astronomical studies appear to date from the Middle Babylonian to Neo-Assyrian periods, from about 1200-600 BCE, of these, the earliest pair of documents listing constellations is the Mul Apin (7th century) (Hoffmann & Krebernik 2023).

Mesopotamia introduced the Zodiac that we know in the 5th century BCE, during the Persian empire. Similarly the mathematical astronomical tablets that Babylon is famous for all date to this time and later, over 150 years after the date of the planisphere (de Jong 2007, Ossendrijver 2013, 2020, Sallaberger 2021, Koch-Westenholz 1995).

It is in the British Museum in London (k.8538, CDLI P397674).

|

| The replicas are fairly easy to recognise |

The cuneiform information on the sphere is currently attributed a date of 3rd of January 650 BCE from calculations of the position of constellations above the horizon over Nineveh made by Assyriologist Johannes Koch in 1989.

Bond and Hempsell briefly cite this book in their introduction under - conclusions reached by other researchers - but either did not read it or simply chose to ignore this research.

Bond and Hempsell 2008

Their translation is a dog’s breakfast

In fact, their claim is hyperbole intended for media promotion, as in the book they state that they used King’s 1912 copy of the planisphere (above left) in combination with two academic dictionaries (Labat 1976, Borger 1978) and one by an amateur (Halloren 2006).

They also cite Weidner 1915, who attempted the first identification of the constellations, but how much attention they gave his conclusions is debatable. For much of the book it appears they only adopted his identification of a few star groups and then relied on the King diagram and the dictionaries.

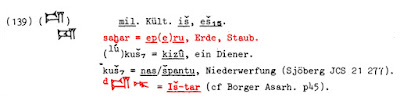

They make umpteen errors translating Sumerian

Therefore, translations in this book contain multiple errors or willful changes of sign or meaning to suit the authors' theories. I might add that while they acknowledge that the disk is written in Akkadian they always translate the signs in Sumerian values.

However, for this I will only provide one example of their methods:

The sign they call 'ŠAR'.

Firstly, it is important to be aware that one sign can have many written values in Sumerian and Akkadian (the language of Assyria and Babylonia). In addition these signs can have multiple nuanced translations, depending on culture and context, and they can be used to construct other words.

In addition, signs can have superficially similar written forms (in English), yet these may otherwise be unrelated. For example, the value 'ŠAR' (shar) has 7 separate cuneiform signs that are differentiated by a numbering system. All cuneiform signs are ordered in this way.

Then they conclude that it marks the horizon, ignoring the signs preceding and following.

Here’s the deal.

What has puzzled people is the inconsistent mapping of identifiable star groups, and the strange use of sign repetition on the sphere, like AN AN AN AN, EN EN EN or ME ME ME.

Bond and Hempsell concluded that the repetition was used to indicate whether the sky was clear (AN, BAD), dark (ME) or cloudy (EN, NA) in different parts of the sphere. Or, as already stated, by claiming this denotes the horizon. They did this by selecting loose translations of signs and then modifying these to suit their theory.

Rather than say looking up the correct cuneiform terms for these phenomena.

Sometimes this involves changing signs entirely, on the basis of the sounds-a-bit-like method, like changing ME ('being') to ME2 ('dark/black/night'), again because these sound similar in English. They dress this up to look legitimate by calling it homophony. However, the signs themselves are different (see ePSD).

|

| 'it is assumed' |

Then they simply ignore the sign repetition that does not suit their argument.

Oh and inventing connections that do not exist.

The sphere is not an astrolabe, or in fact a planisphere in the correct sense of these words, it is an astro-magical or astro-mystical document (Monroe 2022).

Mesopotamian astronomy knew 7 planets (incl. Sun and Moon) that were regarded as gods and therefore could be preceded by the sign for god (AN/dingir) or star (MUL) in astronomical texts. All celestial bodies, stars, constellations and planets had specific names and divine titles.

Assyriologists have documented these for over a century (see Horowitz 1998, Brown 2000, Reiner 1995, Hoffmann & Krebernik 2023).

I would have thought this might be a singular handicap to finding a date to fit your astronomical model. Undeterred by such trivialities Bond and Hempsell proposed two solutions:

2) No-evidence-doesn’t-mean-evidence-didn’t-exist – so they suggest the planets might have been on the missing sections.

|

| 'it is speculated' |

At one point speculating that the repetition of the sign EN (actually 'ruler', 'master' or 'lord') could indicate 4 planets on the sphere. Then over the page they argue that this line of ENs means a wall of cloud in a clear sky, because the Sumerian sign EN was based on a wall, due to rulers building walls (also their speculation).

They go on to argue that two unidentified dots in this section must be Mercury and Jupiter.

|

| This image appears to place constellations inverse to the other charts (below), B & H 2008. |

Nonetheless, the names on the planisphere have enough matches to the Mul Apin lists (named after a constellation) that it has been possible for Assyriologists to identify stars and constellations. For example, these represent parts of our Taurus, Gemini, Orion, Canis Major, Pegasus, Libra, Virgo, Pisces, Cassiopeia and Andromeda, with stars like Sirius, Bellatrix and Betelgeuse (Koch 1989).

|

| The star group Mul Apin (Plough) is incidentally on the planisphere. |

NOT the 32nd century BCE.

Koch (1989) argued convincingly that the eight segments of the planisphere were meant to be rotated by the holder to align with the direction of the cuneiform signs and designs, and therefore were viewed individually.

|

| Note the sections containing the asteroid's path and debris plume (lower right) |

Which has the result that they often identify different constellations in their reconstruction in order to make the planisphere an accurate representation of the night sky on the date that they have chosen, inclusive of both an asteroid pass over and a post impact debris plume.

This also involves such innovations as claiming details about whether the sky was clear or cloudy over different parts of the sphere. Something that if it were true would be unique for Mesopotamian astronomical spheres.

In addition, they conflate AN 'sky' with MUL 'star', arguing that a solitary AN could also be read as MUL, because the original Sumerian value was a star and the silly Assyrian copyist has mistaken a star for stars.... oops.

But I am particularly fond of their rationalisation for the identification of the Milky Way:

Orion was called SIPA.ZI.AN.NA, 'the True Shepherd of Anu' in Assyro-Babylonia in the early 1st millennium.

Basically, AN has whatever value they consider fits their argument: sky, star, clear sky, Milky Way etc.

.jpg) |

| AN/dingir in Dumuzi and 'great god', the tail end of Ishtar is far left. |

Except dingir 'god', or 'Anu'

Dumuzi, Enlil, Ishtar, Lulal, Latarak, Ilabrat, Papsukkal and Anu, for example.

1) Like for - dingirDUMU.ZI / ilu rabu (AN GAL) - 'Dumuzi' / 'great god'

Bellatrix was called [Papsukkal] 'the vizier of Anu and Ishtar' and this name is incidentally written adjacent to the name of Orion along with the god Ilabrat who was also associated with both gods.

The most impressive aspect of this is that B & H looked up the sign IŠ in Borger and Labat then ignored that it is part of the name Ishtar when combined with the exact signs that are preceding (dingir -'god') and following (TAR), and instead they chose 'dust', 'sand' or 'dirt' (SAḪAR).

|

| Labat 1976 |

3) Lastly, for their text given below - LUGAL LU2 MUL LA TA SAL - they have altered the sign AN to MUL and included an error from King 1912 (LUGAL), which aptly demonstrates their indifference to later translations, as Weidner corrected this misreading in 1915, as did Koch in 1989.

(There really ought to be a face-desk emoji)

This gleefully cavalier approach is applied consistently throughout to the translation of individual cuneiform signs, the names of stars and constellations... What I have provided here is just grotesque highlights... therefore the entire argument is driven by their beliefs and not by evidence, nor by any understanding of cuneiform.

Basically, if you accept that the translation of a language is somehow authorative, you cannot just pick and choose what of that authority you like, ignore the rest and then claim you have created a new translation.

Either you accept that authority or you need to provide a completely new translation model... good luck with that.

|

| This example sums up their questionable methods for me. |

Conclusion

Although I had my doubts when it came to the claims circulated in bullshit memes on the internet. But I assumed much of this was hyperbole. I also assumed that the many people providing links online to the Museum information about the sphere would kill this myth in time.

I was wrong on both counts.

Their translations of Sumerian are a mixture of copying out early Assyriological studies of the sphere, combined with playing Pin-the-Tail-on-the-Donkey in dictionary searches, and are textbook examples of amateurish arrogance. Context and experience are crucial in understanding ancient languages.

- Little or no evidence disguised in speculative proposals

- Vague language: 'it is speculated', 'assumed', 'suggested', 'presumably', 'could be'

- Use of the no-evidence-doesn't-mean-the-evidence-doesn't-exist rationalisation

- Hyperbolic claims of groundbreaking research or translations

- Cherry picking data to fit theory

- Altering or inventing data to fit theory

- Selective use of academic authority while also dismissing academic authority

- Using out of date academic literature and/or not enough literature

- Citing pseudoscience as literature

To sum up: Pseudoscience boxes ticked

None of Bond and Hempsell's claims stand up to scrutiny:

January 2024

A word of thanks to Dr Janine Wende of the Assyriology institute in Leipzig for providing constructive input about the Assyriological content.

But don't trust me: Read further

Sciency stuff: Köfels event

Websites

EBL: Electronic Babylonian Library - https://www.ebl.lmu.de/fragmentarium/K.8538

Halloren, J.A. 2006. Sumerian Lexicon - https://www.sumerian.org/sumerlex.htm

Texts cited in this blog and general reading on Meso astronomy

Horowitz, W. 1998. Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography. Eisenbrauns.

de Jong, T. 2007. 'Astronomical Dating of the Rising Star List in MUL.APIN.' Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes: 107-120.

King, L.W. 1912. Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum 33. British Museum.

Koch, J. 1989. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des babylonischen Fixsternhimmels. Harrassowitz.

Koch-Westenholz, U. 1995. Mesopotamian Astrology: An Introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian Celestial Divination. Museum Tusculanem Press.

Monroe, M.W. 2022. 'Astronomical and Astrological Diagrams from Cuneiform Sources.' Journal for the History of Astronomy 53(3): 338-61.

Ossendrijver, M. 2013. 'Science, Mesopotamian.' The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, R.S. Bagnall, K. Brodersen, C.B. Champion, A. Erskine and S.B. Hübner, 6070-2.

Ossendrijver, M. 2020. 'The Moon and Planets in Ancient Mesopotamia.' Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Planetary Science. Oxford.

Reiner, E. 1995. 'The Uses of Astronomy.' JAOS 105(4): 589-95.

Rochberg, F. 2004. The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge.

Sallaberger, W. 2021. 'The Emergence of Calendars in the Third Millennium BC.' Calendars and Festivals in Mesopotamia in the Third and Second Millennia BC, D. Shibata & S. Yamada (eds). Harrasowitz.

Weidner, E.F. 1915. Handbuch der babylonischen Astronomie: Der babylonische Fixsternhimmel. Hinrichs.