|

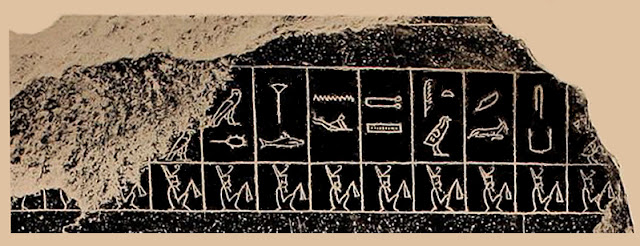

| Horus of Behedet, the winged sun disk. Image A. Sinclair 2017. |

I am only nominally into the prehistoric of Egypt, as my real preference has always been that

of Sumer, the Uruk period. As

it happens it is only serendipity that I did not do my studies there,

but the professor of Near Eastern studies was on leave and I knocked on another

door entirely, so now I am in the Late Bronze Age.

But rather than talk about the vagaries of my life, today

I am going to look at the Egyptian Predynastic, or at least some mythology

about it. A quick internet search of ‘Shemsu Hor’

will supply my motives for writing this, as it will result in an

abundance of nonsense from pseudo-history websites, often all

joined by a common passion for the word Ancient.

If you are ‘lucky’ it will also link you to free-to-read books

from the dawn of time, which is also my motivation for writing this. Out of copyright is often a curse, because

the general public and lazy journalists have access to scholarship that

is out of date and embarrassingly flawed, oh, and often racist to boot.

So today I am going to walk you through the history of scholarship on the followers of Horus, the Shemsu Heru or Shemsu Hor, legendary proto-kings of ancient Egypt, beginning with the reliability of the Greek historian Manetho.

So today I am going to walk you through the history of scholarship on the followers of Horus, the Shemsu Heru or Shemsu Hor, legendary proto-kings of ancient Egypt, beginning with the reliability of the Greek historian Manetho.

But before we go there you are getting a very brief

overview.

Dynasties

Pharaonic Egypt is measured from the 1st Dynasty of the Old

Kingdom, beginning around 3000 BCE, which probably represents the point that

Egypt was unified under one king, and it lasted about 2700 years until the 31st

Dynasty when the final king was deposed by Alexander’s armies in 332 BCE. Although to be purist it could be the 27th

Dynasty when the Persians conquered Egypt.

Regardless,

this dynastic system was how the Hellenistic

historian Manetho wrote up the kings of Egypt, and this tends to be how

Egyptologists differentiate the various families, kingdoms and eras

chronologically, even now, because classics has always

been the foundation of Egyptology.

In Egyptian state symbolism there was great emphasis on

Egypt as two separate regions united together under a strong king: these two halves were

northern or Lower Egypt (Delta region) and southern or Upper Egypt (south of Cairo). The

Upper and Lower refer to

travelling up or down the Nile river. The ancient Egyptians really

liked the idea of united duality: chaos and order, wild desert and

fertile Nile valley, north and south kingdoms, dual kings.

|

| Version of Manetho by Syncellus (9th century CE). |

Horus

Horus (‘Ḥrw’or ‘Ḥr’ - Heru or Hor) was a very important falcon god associated

with the sun in the Egyptian pantheon, but he took many, not always related,

forms, particularly in the early periods.

There was not one Horus in Egypt, rather there were a few, who could

have different characters and actions, and could be sons of the underworld god

Osiris, or of the sun god Re. These get mixed and matched and merged together in the later periods.

We are interested here in the falcon headed god who was associated

with kingship from about the early Middle Kingdom in Egypt; the son of Re, Horus of the

region of Edfu (Behedet), and in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, the Horus of

Nekhen (Hierakonpolis). The Egyptian

king was always considered son of the sun god, a semi-divine incarnation of Horus.

Manetho – Aegyptiaca Book I

Manetho wrote his history of the kings of Egypt in the 3rd

century BCE during the Hellenistic period, well after the pharaonic period,

however no copies of his original text have survived. This means that when a text says ‘Manetho

wrote’ – they actually mean ‘Syncellus said that Eusebius

said Manetho wrote

…’, or ‘the Armenian version of Eusebius said that Eusebius

said that Manetho said …’

So the example of artistic licence here is any source stating

that these texts were written in the 3rd century BCE, when in fact most were

written around a 1000 years later by Christian monks from copies of

copies. Oh and the copies do not

match each other, unsurprisingly, so when Manetho is quoted as saying ‘this

many years’ or ‘this god king’ the writer is citing the text they like best,

and ignoring the rest, assuming they are not simply improvising.

The golden age of kings

To make this as brief as possible, for the period before

human kings Manetho wrote of 3 earlier mythical eras; firstly Egypt was

ruled by the gods (the number and gods vary) usually ending with Orus (Horus) –

then came demigods (ημιθεοι) – and after these the manes or spirits of the dead, νεκυες

οι ημιθεοι (‘half-divine dead’), who ruled for 5,813 years (Armenian Eusebius) or 2,100 years (Excerpta Latina Barbari).

The translator of the LOEB edition Waddell (1940) then adds

a footnote: ‘These are perhaps the Shemsu Hor of the Turin Papyrus - men of the

falcon clan whose original home was in the western Delta, had formed an earlier

united kingdom by conquering Upper Egypt’.

So to begin – the followers of Horus or Shemsu Heru (Šmśw Ḥrw) are never mentioned

in any version of Manetho.

Wilkinson 1879 Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians

I am starting my history of modern scholarship with Sir Gardner Wilkinson because this is a ‘highlights

of’ and he is a good place to start for misinformation about this topic.

He

opens his 3 volume work with an historical overview of pharaonic Egypt

and a problematic

discussion of race in which the words ‘Nigritic’ and ‘Aryan’ get an

airing. He also throws in the theory of 4 ancient races that honestly

will have to get its own article, as the pseudos love it. His racially

motivated narrative then develops into a discussion of whether the

Egyptians were native to north-east Africa, or

were asiatics or arabs. The biblical story of Ham is used to support

this.

He plonks for the invasion option, citing the shasu en har, or followers of Horus as the primitive peoples who lived in Egypt before the pharaonic Egyptians drove them from the country, however his writing is unclear and I cannot exclude that he actually meant that the followers were the invading ‘Egyptians’ … either way, ouch.

He plonks for the invasion option, citing the shasu en har, or followers of Horus as the primitive peoples who lived in Egypt before the pharaonic Egyptians drove them from the country, however his writing is unclear and I cannot exclude that he actually meant that the followers were the invading ‘Egyptians’ … either way, ouch.

This sets the tone in Egyptology for the next 50 years.

Maspero 1894 – Dawn of Civilisation: Egypt and Chaldaea

Gaston Maspero in writing his history of Egypt and Babylon

in a nice evocative manner a few years later made the rookie mistake of

choosing to open a chapter on Egyptian political structure with a little

licence, stating that the ‘Great Sphinx Harmarkhis has mounted guard over the

Giza plateau’s northern extremity since the time of the Followers of Horus’.

This one piece of poetic embroidery has since supplied pseudo-numpties with

fuel for an argument that the sphinx must therefore be older than the pyramids

… ‘look Maspero said it (125 years ago) … it must be true’ (see Ancient Code

2015, or Hancock and Bauval 1997, who milk this angle and go on to misrepresent what he wrote).

The

sphinx is btw about 500 years later than the end of the

Predynastic, and it was carved sometime during the 4th Dynasty

(2520-2392 BCE), only people with no background in archaeology argue

this point. Maspero was perhaps thinking of the followers

of Horus that are mentioned in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts.

But earlier, his brief mention of the followers of Horus

assumes that they were the military entourage of the god Horus during his

exile and in the battles for control of Egypt with the god Typhon

(Seth). These followers were then

deified after death by their grateful master.

He cites the names on the Turin king-list and adds a dash of creative

transliteration; calling them the ‘Shosûû Horû, but sensibly notes that for the

pharaonic Egyptians these kings lived beyond the point where history reached.

Maspero is also the original source of the claim that the followers

were blacksmiths.

Budge 1902 – A History of Egypt

The director of the British Museum in the Victorian era

EAW Budge based his interpretation of the prehistoric period on Manetho, using mainly

the versions by Eusebius and Panodorus, stating that the eras of reign of gods and demigods, ‘primeval chiefs’ or

‘heads of tribes’, were about 12,843 years or 11,831/2 years long.

Then he airily states there can be no doubt that the Spirits

of the Dead of Manetho were the Shemsu Heru mentioned in ancient Egyptian

literature. He goes on to add insult to

injury by arguing these followers of Horus were chiefs of a race who came to

Egypt from the east via the Delta and brought ‘a higher grade of civilisation’ to

Egypt by conquering the aboriginal north-east African race and then ruling in

Upper and Lower Egypt.

This

idea that an advanced race introduced technology and civilisation to

Egypt is now debunked and with Wilkinson is a textbook

example of western colonialism at its most arrogant. It is

also perpetuated today by pseudo sources such as Ancient Origins (2017)

Ancient Pages (2017), Andrew Collins (2002) and Graham Hancock/Robert

Bauval (1997).

However, Budge almost hits the nail on the head by assuming

that the Abydos tombs excavated in 1900 could have belonged to these ‘followers’ who were the kings

of Upper Egypt: Khent, Te/De, Re and Ka. For Lower Egypt he cites kings on the Palermo Stone

king-list; Mekha, Uatch-Nar, Neheb, Thesh, Tau, Ṭesau, Seka,

.

Some names must be taken with a hefty spoon of salt, his transliterations are often obsolete, so for the list above from left to right: king of the red crown Mekhet, Wadjbu or Wenegbu, Neheb, Tjesh, Tiu, Khaiu, Seka.

Some names must be taken with a hefty spoon of salt, his transliterations are often obsolete, so for the list above from left to right: king of the red crown Mekhet, Wadjbu or Wenegbu, Neheb, Tjesh, Tiu, Khaiu, Seka.

The Palermo king-list btw does not match any version of

Manetho for the Predynastic kings and none of these kings are known from any other sources.

Sayce 1903 – The Religions of Ancient Egypt and Babylon

A year later Sayce repeated the foreign conquerors thesis by claiming

these followers of Horus and a historical king Horus were probably invaders from

Babylonia, which is epic when you consider the Sumerians were running

Mesopotamia in about 3500 BCE. These, probably

coincidentally quite white heroes, conquered the primitive races and created

civilisation in Egypt.

We call this diffusion theory: where western scholars tried

to prove that civilisation began in one place and then spread west towards Europe by

conquering or migration to neighbouring primitive cultures. This theory went out of circulation in archaeology between 1950 and 1970.

Sayce also reinforced the career choice that is still sometimes

employed (by amateurs) for the ‘Shesh Hor’ – that the followers of Horus were

blacksmiths – ‘mesniu’. Your first

warning bell btw should be the old fashioned word ‘blacksmith’, because in

archaeology we prefer to use ‘metalworker’ or even ‘smith’ for this job skill.

This name, mesnu (msnw), is from the ‘Legend of the Winged Disk’ that

describes the battles of Horus and Seth and is written on the walls of the temple of Horus

Behedety at Edfu in Upper Egypt. Firstly, it should be

emphasised that this is a post-pharaonic mythological text from the same period as Manetho,

or later (Edfu was built between 300-142 BCE).

Secondly, the translation of msnw is incorrect.

The followers of Horus were

called ‘the harpooners’ and they are depicted at Edfu with him wielding

harpoons and knives against the hippopotami that represented Seth and evil. This isn’t exactly new news, in 1918 Kurt Sethe

refuted the translation of mesniu as ‘blacksmith in ‘Die Angeblichen Schmiede

des Horus von Edfu’ (‘The Alleged Blacksmiths of Horus at Edfu’).

Msnw, which is determined with a

harpoon sign, not a crucible (for metalworkers), has been translated this way for about 100 years.

Sorry no blacksmiths, no ironworkers.

Many early 20th century writers have repeated this error and

a few later ones as well.

Pro tip: if someone claims the Shemsu Heru were blacksmiths

you can assume they used an early text, regardless of whether they cite a

later publishing date (an old trick).

Hancock and Bauval (1997) for example used Maspero (above) and

every Dover re-edition of EAW Budge they could track down. Budge died

in 1934, he definitely was not publishing between 1969 and 1980.

| |

| The same text by Budge and Fairman. What a difference 20 or so years can make in Egyptology. |

Sethe 1905 – Beiträge zur Ägyptische Geschichte

Kurt Sethe was a solid linguist and is a much safer source

than say Budge, Wilkinson or Maspero. He therefore

approached the topic from that point of view. His transliteration and interpretations are

for his era still valid - the Šmśw-Ḥr (Shemsu Hor) ‘those who follow Horus’ or

‘successors of Horus’ or even ‘servants of Horus’.

In this he briefly summarised earlier findings with the

conclusion that these Shemsu Hor were the kings who succeeded a king Horus in the

Predynastic period after the supposed rule of the 9 great Ennead gods. Their successors therefore being the lesser

Ennead, who were the half gods and half-divine spirits of Manetho.

But he tweaks the model with the statement that the term ‘shems’

– Šmś may be translated as ‘follow’, but it was also used to express ‘to serve (a king)’, therefore the Šmśw-Ḥrw must have been

beings who served Horus and filled in the time between the god king and the

first dynastic king Menes.

However, the word can be used for ‘worship’, as well as ‘follow’,

or ‘serve’, and the followers of Horus could have been human men who worshipped

the god. A Middle Kingdom text from

Asyut names the followers as gods with the bodies of jackals – from this he

emphasises that these kings were deified after death.

Therefore they were Manetho’s dead half-divine kings.

Therefore they were Manetho’s dead half-divine kings.

From real dead kings of the Egyptian Predynastic Sethe moves to

his own argument that the Shemsu Heru were in fact the prehistoric rulers of

Upper and Lower Egypt at Nekhen (Hierakonpolis) and Pe (Buto). He then equates them with the ancestors of kingship, the Souls of Nekhen

and Pe, and suggests that they were later also associated with the Sons of

Horus.

Budge 1934 – From Fetish to God in Ancient Egypt

Mr

Budge approaches the Followers differently 30 years later,

by basically dumping blacksmiths, and arguing that

these mythical beings were hawk or jackal headed divinities, whose names

were written with jackal or

hawk standards and the signs for the bow

and throwstick. This assumption is based on the writing of the name in

the Pyramid Texts, and on depictions of the Souls of Nekhen and Pe.

However, here he says the Shemsu were the companions of Horus of

Edfu, whom he assumes was a real prehistoric king, or they were the kings

who immediately followed his reign. He contradicts Sethe rejecting the argument that the Souls of Nekhen

and Pe were the Shemsu Heru. These instead must have been the early kings of those cities, while

the followers were the royal successors of Horus.

Confused yet? That is

basically how the topic was handled 100 years ago: by trying to fit later sources like Manetho, the

scant textual evidence and some actually archaeology together, when they don’t

match, all the other important pieces are missing, and it is likely both

Manetho and the late Egyptian texts have errors.

Helck 1956 –‛Untersuchungen zu Manetho und den Ägyptischen

Königslisten’

Wolfgang Helck was a kick-ass linguist of a few generations

back who used the same sources, but sensibly emphasised the vast difference

between the many late classical texts (like Manetho) and the actual ancient

evidence, which led him to a discussion of how early the Egyptians documented time

and years of kingship.

He began with the introduction of the bi-yearly cattle

count and the royal procession through Egypt to record this event which was

instituted in about the 3rd Dynasty (2584-2520 BCE). The procession was incidentally also called

the shemsu Heru, but this time it refers to the ‘following/procession of Horus (the

king)’, who was considered to be the earthly incarnation of Horus.

Another

thing that people may mix up, including no doubt the

pharaonic Egyptians, shem – ‘follow’ was a relatively common term, as

both a verb and noun, just like in English, and it was a title that also

applied to the retinue of the king.

|

Shemsu/followers of king Niuserre from the Sun Temple of

Niuserre near Giza.

5th Dynasty, Old Kingdom.

Image from Borchardt 1907, pl 16.

|

After the beginnings of record keeping in Egypt, the earliest

document that lists kings is the Royal Annals, which includes

the famous Palermo Stone. The various fragments

from this monument date from the 5th Dynasty, ca 2392-2282 BCE. However, the Palermo Stone is the only useful

fragment to us and it names 7 kings of Lower Egypt for the

Predynastic (already mentioned with image above for Budge 1902).

The Palermo Stone does not mention the Shemsu Heru (nice try

Ancient Code), but much of the text is missing.

After this king-list, Helck introduced the evidence from the

18th Dynasty, which is around 1000 years later than the pyramids; on the Tombos stele of king Thutmose I (ca

1500 BCE), and later from the Turin king-list papyrus (19th Dynasty, ca 1250 BCE). Both texts briefly mention the Shemsu Heru as being early

kings of Egypt.

So

by the 18th Dynasty

at least, they were an integral part of the mythological past, and were

believed

to have ruled in the time after the rule of the gods, however the term

had also evolved to apply to any loyal follower of the king's retinue,

who from his service to the living Horus could become a follower after

death.

Helck

also rejected Sethe’s theory that these kings were the early kings

of Nekhen and Pe, citing the Papyrus Prisse as support (12th Dynasty, ca

1800

BCE). However, this source actually contributes little to the issue, as

it is

a brief reference to the followers of Horus in a how-to-guide for

correct behaviour for a man from the Instructions of Ptahhotep.

|

| Middle Kingdom, translation from VA. Tobin 2003. |

Gardiner 1961 – Egypt of the Pharaohs

Nearly ten years later another giant of Egyptology Alan

Gardiner devoted a few pages to the Predynastic by repeating what we know

from Manetho, that Egypt was ruled by gods, half gods and souls of the dead

before the Old Kingdom. From there he moves to the names on the Turin

papyrus and says these must be the followers of Horus who Sethe ‘rightly diagnosed’

to have been the early kings of Nekhen and Pe, but he gets a jab in by saying Sethe

supplies little supporting evidence.

This oversight is then fixed by citing an unspecified Roman period papyrus (only 3000 years away from reality) that states that the souls of Nekhen were followers of Horus as kings of Upper Egypt, and the souls of Pe were these as kings of Lower Egypt (‘as Griffith pointed out orally to the present writer’, cos in 1961 this was totally cool, nowadays peer reviewer no. 2 would hang you out to dry for it).

This oversight is then fixed by citing an unspecified Roman period papyrus (only 3000 years away from reality) that states that the souls of Nekhen were followers of Horus as kings of Upper Egypt, and the souls of Pe were these as kings of Lower Egypt (‘as Griffith pointed out orally to the present writer’, cos in 1961 this was totally cool, nowadays peer reviewer no. 2 would hang you out to dry for it).

Anyway, from Manetho’s versions, Sethe’s 1902 article, and

an unnamed Roman papyrus Gardiner concluded in 1961 that two separate ancient kingdoms

ruled Predynastic Egypt in the south at Nekhen and the Delta at Pe before 3000 BCE and before the unification

of the state under king Menes.

Edwards 1970 – Cambridge Ancient History

Another big name who opens his chapter on the Early Dynastic

with a careful statement that: ‘Tradition and a substantial body of indirect

evidence suggest strongly that Egypt, in the period immediately preceding the

foundation of the first Dynasty, was divided into two independent

kingdoms.’ A northern kingdom at Pe, and

a southern kingdom in Upper Egypt at Nekhen near Edfu, both of which possessed

important sanctuaries of the falcon-god Horus, the patron god of kings.

He goes on to cite the Palermo stone and Turin king list, sensibly

emphasising that these texts are largely lost and ‘what remains is difficult to

interpret’. He sites all the sources

given so far including the unspecified Roman era papyrus of

Gardiner, while also making it very clear that he assumes this is a very late

confusion of the followers of Horus with the souls of Nekhen and Pe.

Finally, he turns to archaeology and cites the two Predynastic

kings that were known from archaeological records at that time; Ka and Scorpion,

whom he assumes therefore could have been the model for Shemsu Heru kings.

Pinch 2002 – Handbook of Egyptian Mythology

Geraldine

Pinch sums up the 21st century approach to the

prehistoric narrative by placing it under mythical time lines along with

the other late Egyptian myths of the deeds of the god Horus.

She names 9 akhu spirits who were associated with the governorates of Buto (Pe), Hierakonpolis (Nekhen) and Heliopolis (Iunu), whom the Egyptians believed ruled Egypt after the gods in the Predynastic period. These akhu also included lesser kings called the followers of Horus and together – are quasi myth – part of ancient Egyptian mythical time.

She names 9 akhu spirits who were associated with the governorates of Buto (Pe), Hierakonpolis (Nekhen) and Heliopolis (Iunu), whom the Egyptians believed ruled Egypt after the gods in the Predynastic period. These akhu also included lesser kings called the followers of Horus and together – are quasi myth – part of ancient Egyptian mythical time.

She emphasises the reign of the god Horus was

the prototype for Egyptian kingship, an idyllic time where evil was unknown,

and therefore it served as the model for all Egyptian kings in the pharaonic

period, who also represented Horus and divine kingship on earth, and who were

tasked with maintaining universal order.

Which finally brings us to the most important source for the

followers of Horus.

|

| Reconstruction of the Turin king-list in standard hieroglyphs. You want columns 1-3. Image from Wikipedia. |

Ryholt 2004 ‒ The Turin King-List

The Turin king-list is not a royal canon, but rather a

list of about 300 kings regardless of favour or character written on a 2nd

hand papyrus, probably as scribal practice. Written in hieratic on the back of a tax list and

dated to the reign of Ramses II (13th century BCE), it was probably based on

tradition and copied from earlier copies that were not without errors.

It is very fragmentary due to severe damage while travelling

on a donkey in the 1800s. A lot of names

are lost, what remains are mostly damaged. This

papyrus is a list of Egyptian kings from the mythological period to historical

dynasties up to the New Kingdom. They

are loosely divided into 3 groups; god-kings, akhu spirits and historical kings.

1) Gods and demi-gods – Ptah, Geb, Osiris, Seth, Horus,

Thoth, Maat, Amen are listed (in Column I-2 more than half the names are lost). Horus is named 3 times, Seth twice, and a

king called Shemsu at line 2.4.

2) Spirits / akhu kings (Columns 2-3.9) are all damaged. Two

Shemsu Heru are named on line 3.8 and 3.9, but the ‘akh’ is missing and assumed

to be there. The names are damaged

and the year numbers may be incomplete; 3.8 (reign 3420? years) & 3.9

(3200? years). Again, these akhu are assumed

to be Predynastic kings, but not to be historically accurate, rather a part of

mythological time.

3) The historical section of the list begins with Menes, the

first king of the 1st Dynasty. The

historical king names do not match Manetho particularly well, he has errors,

this has errors. But the groups of early divine kings match the later text in a general way.

Therefore, from what little info is supplied there in the Ramesside period, the kings who

we know predated Menes all may have been the akhu kings

or the models for the Shemsu Heru – that is the Dynasty 0/Naqada III kings like Scorpion, Crocodile,

Iry-Hor, Ka and Narmer (who may be Menes).

However, the Turin list does not match any of the early kings on the Palermo Stone, nor the versions of Manetho, and it has errors for later kings.

However, the Turin list does not match any of the early kings on the Palermo Stone, nor the versions of Manetho, and it has errors for later kings.

So in fact there is no complete or absolutely accurate king-list from

pharaonic Egypt.

|

40,000 years, I must have missed that ... oh and

the gods of the first time,

the ‘moment of creation’ were Atum, Shu and Tefnut.

|

In conclusion

The documentation of kings and of year names was developed

in Egypt long after the Predynastic period, so any and all prehistoric

kings were never accurately recorded in pharaonic Egypt. Therefore the later records may have

been based on oral legends, or simply devised to explain the Shemsu Heru’s

function within religious myths, temple ritual and within Old and Middle

Kingdom funerary texts.

By the New Kingdom (1500 BCE) there had been plenty of opportunity

for ideas to evolve, and for misinformation to be passed down formal and

informal channels, which continued to accumulate more than 1000 years later, by

the time of Manetho. Then Manetho’s Aegyptiaca

itself disappeared and became a series of garbled anecdotes from the Roman and

early Christian periods.

This is the point where academics began in the early 1800s

when trying to untangle Egypt’s history.

Therefore, if we ignore the later anecdotes, there is very little evidence of these Shemsu Heru kings from pharaonic Egypt. A brief reference in the Turin papyrus mentions akhu spirits who were kings of Egypt after the gods and before the dynastic kings and another names a god king called ‘follower’. The Palermo Stone simply names 7 kings of Lower Egypt.

Therefore, if we ignore the later anecdotes, there is very little evidence of these Shemsu Heru kings from pharaonic Egypt. A brief reference in the Turin papyrus mentions akhu spirits who were kings of Egypt after the gods and before the dynastic kings and another names a god king called ‘follower’. The Palermo Stone simply names 7 kings of Lower Egypt.

The followers of Horus in turn became a metaphor for a loyal

servant of the king and honourable nobleman in Middle Kingdom instruction texts

(Ptahhotep). New

Kingdom courtiers hoped

to become ‘a follower’ after death, like the official Kheruef had

written in his tomb at Thebes. Pharaoh Thutmose I bragged on a piece of state

propaganda that what he had done for his followers had not been seen

since the

rule of the followers of Horus.

In earlier Old Kingdom funerary texts, particularly the Pyramid Texts of

the 4th Dynasty, the followers of Horus are gods who cleanse the deceased,

provide natron salt for purifying his speech and they voice their approval for

him to join the gods. They rally beside

Horus and the deceased king in the rituals for regeneration and in the eternal

feud with chaos and the followers of Seth.

Which is totally consistent with ancient

Egyptian thought, once a king died he joined the gods, he then became

part of the universal cycle of order and the battle with chaos. The distant Predynastic kings who ruled parts

of Egypt before it was unified, became the stuff of legend,

and like the mythologies of many ancient cultures their numbers of reign were made

awe-inspiringly long.

End

Magical pasts are attractive to humans and the Egyptians of

1200 BCE and 300 BCE were as receptive to myth, fantasy and tales of idyllic pasts as

the millions who subscribe to pseudo-history websites and hungrily buy their

embellishments of meagre evidence.

But the Egyptians had a better excuse, this was their belief system,

how they thought the universe worked. We don't have this excuse.

Although I must confess the Shemsu Heru are a perfect opportunity

for ringing those pseudo cash registers, as there is very little actual evidence of

them, if you ignore the out of date texts that fraudsters rely on to vamp

up their stories. All we really know is

that the ancient Egyptians, like nearly any other culture, believed their mythical

early kings were gods or divine spirits of the royal dead, beyond that little else.

So you can basically make anything up under those

circumstances, like the followers of Horus were initiates in an elite academy of

astrologists at Heliopolis (Graham Hancock/Robert Bauval), reptilian illuminati

aliens (Chris Thomson), alchemists of an advanced civilisation from 10,000 BCE (Andrew

Collins/William Henry), keepers of alien sacred knowledge (Ancient Pages/Collins), 15 metre

tall giants (Ancient Origins), invented the pyramid and sphinx in an

earlier Atlantian age and brought civilisation to the primitive natives (Ancient Code/Pages/Hancock/Collins,/Bauval)

… and so on.

And due to lack of any images to put with these stories you

can instead pad them out with fan fiction artwork that looks like it was stolen

straight out of a computer game…. or more likely Pinterest.

The punters will love it.

Andrea Sinclair

2020

PS: Seriously guys, stop believing books written in 1900 are

accurate. Publishers today publish these

cos it’s dirt cheap, and they prefer to avoid paying royalties to a living author. Before you buy that cool book on

ancient Egypt, please check its first edition date.

And hey, who hasn’t started with Budge? I understand, honestly... we all started there... I bought every Dover reprint at the

age of 15, and read them til they were grubby, but apart from availability and cool

pictures, he is pretty useless if you are genuinely interested in the ancient

world.

And to the pseudos who are still citing obsolete

translations from 1905, and esoteric nonsense from 1923, upgrade your sources,

you lazy (and cheap) shits.

Further reading and sources

Pseudo, esoterica and ‘blacksmiths’

Brown, B

1923. The Wisdom of the Egyptians: The

Story of the Egyptians, the Religion of the Ancient Egyptians.

Collins, A.

2002. Gods of Eden:

Egypt’s

Lost Legacy.

Gordon, JS. 2015. Esoteric

Egypt.

G. Hancock, G and

RG. Bauval 1997. Message of the

Sphinx.

Henry, W.

2006. Oracle of the Illuminati.

Ancient Code

2016. ‘Shemsu Hor, the Celestial

architects of the Great Sphinx, an 800,000 year old monument.’ & ‘Turin Royal Canon: An Ancient Papyrus that

proves ‘Gods ruled over Ancient Egypt.’

Ancient Pages 2017. ‘Mysterious

Shemsu Hor – Followers of Horus were Semi-Divine Kings and Keepers of Sacred

Knowledge in Predynastic Egypt.’

Ancient Origins 2017. ‘The Giants of Ancient Egypt, Part 1, A Lost

Legacy of the Pharaohs.’

Out of date, colonialist, racist and unreliable, but oh so

retro

Budge, EAW.1902.

A History of Egypt I.

Budge, EAW. 1909. Liturgy of Funerary Offerings.

Budge, EAW. 1912. Legends of the Gods.

Budge, EAW. 1934. From Fetish to God in Ancient Egypt.

Budge, EAW. 1934. From Fetish to God in Ancient Egypt.

Maspero, G.

1894. Dawn of Civilisation: Egypt and Chaldaea.

Müller, WM.

1918. The Mythology of all Races: Egyptian

Mythology.

Sayce, AH.

1903. The Religions of Ancient Egypt and Babylon.

Wilkinson, IG.

1887. Manners and Customs of the Ancient

Egyptians.

Actually worth reading (don't just trust me, check some sources)

Dodson, A. and D. Hilton 2004. The Complete Royal Families of Egypt.

Edwards, IES. 1970. Cambridge Ancient History.

Edwards, IES. 1970. Cambridge Ancient History.

Epigraphic Survey 1980. The tomb of Kheruef, Theban Tomb 192. OIP 102.

Fairman, HW. 1935. ‘The Myth of Horus at Edfu.’ JEA 21.

Fairman, HW. 1935. ‘The Myth of Horus at Edfu.’ JEA 21.

Gardiner, A.

1961. Egypt of the Pharaohs.

Goedicke, H.

1996. ‘The Thutmosis I Inscription near

Tomas’. JNES 55.

Helck, W. 1956. ‚Untersuchungen

zu Manetho und den Ägyptischen Königslisten’. In Untersuchungen zur Geschichte

und Altertumskunde Ägyptens 18.

Pinch, G.

2002. Handbook of Egyptian Mythology.

Ryholt, K.

2004. ‘The Turin King-List’. Ägypten und Levante 14.

Sethe, K. 1905. ‘Beiträge

zur Ägyptische Geschichte’. In Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Altertumskunde

Ägyptens 3.

Tobin, VA. 2003. ‘The Maxims of Ptahhotep’. In The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry.

Tobin, VA. 2003. ‘The Maxims of Ptahhotep’. In The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry.

Waddell, WG.

1940. Manetho with an English

translation by WG. Waddell. LOEB.

Wilkinson, RH. 2003. The Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

Wilkinson, RH. 2003. The Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

Annals/king-lists online

Pharaoh.se website of talented amateur Peter Lundström

(caution; his translations of royal names can contain minor errors): https://pharaoh.se/kinglists