|

| A. muscaria growing under birches in northern Europe. Image A. Sinclair. |

Therefore, attempts to create interesting narratives about the past with the minimum of evidence really do my head in. Evidence that at a stretch would be described as circumstantial if it was a police investigation and a court was in a very generous mood.

In this case however, I doubt it would even get past the officer on the front desk, because this is about the myth of psychoactive mushroom use in ancient Egypt, that, if you did not know, is a bit of a thing in the fringe scene.

The idea being that in Egypt the king or a few superdooper elite priests would consume psychoactive mushrooms during secret rites in order to attain an altered state and ascend to the realm of the gods.

|

| Psilocybe cubensis. Image LordToran at Wikipedia. |

These claims involve two well known psychoactive mushrooms - Amanita muscaria (‘fly agaric’) and Psilocybe cubensis (‘Cuban bare head’). The myths are not particularly new, and blame for this may be laid at the doors of a handful of resourceful fringe authors over the past 60 years.

I will try to keep it brief and only cite the main movers (you can find their groupies easily enough) before ending with the guy who started the ball rolling - Andrija Puharich. This will be followed by a few examples of the claims in contemporary culture. My aim is broad btw, I am not limiting my irritation to the fringes, but to anyone who cites these myths.

We begin with a paper by the individual who is at least partially responsible for my interest in this topic. Some responsibility also lies with an Egyptologist friend, with my partner and his arcane circle of mycophiles, and with the researchers at the Science in Ancient Egypt website who foolishly gave me something interesting to do over the last year.

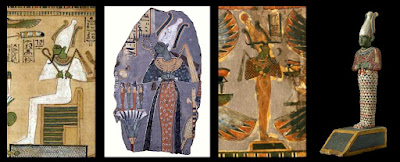

1. The Entheomycological Origin of Egyptian Royal Crowns (2005)

This paper

was followed by the one that now serves as a foundation text for woo about

magic mushies and Egypt – ‘The Entheomycological Origin of Egyptian

Royal Crowns’ - in which Berlant claimed that much ancient Egyptian cult

symbolism and some symbols of kingship were based on the magic mushroom - Psilocybe

cubensis (for a longer review see here).

|

| L-R: Atef, hemhem, white, red & dual crown. Image A. Sinclair. |

The basic premise of this paper is that the white crown of southern Egypt was originally based on the tiny pin (juvenile) form of the P. cubensis. But he argues that other Egyptian crowns were symbols of magic mushrooms, like the red crown, double crown, hemhem, atef and khepresh.

|

| L-R: Amentet standard, Eye of Horus & Abydos standard. Image A. Sinclair. |

14 years

later Berlant expanded his ideas out to two unpublished drafts that include such woo classics as claiming that the practice of celebrating Christmas with

a fir tree is descended from an ancient Egyptian ritual of decorating a fir

tree with A. muscaria... and of the practice of leaving presents around

this tree... in this case A. muscaria caps.

He also argued that the ancient Egyptians force-fed mummies magic mushrooms as the Eye of Horus during the embalming rituals to guarantee their rebirth in the Afterlife, and this (drumroll) is why all Egyptian mummies have their front teeth missing... lol... not all mummies are missing their front teeth... it mostly depends on how old they were at death... Tutankhamen for example doesn’t need his front teeth for Christmas.

|

| Berlant's Xmas tree in the tomb of Roy (19 Dyn). Image Cairoinfo4u at Flickr. |

Berlant’s various claims are extraordinary, yet they are supported by no evidence and mostly illustrate the pitfalls of looking at ancient art when you, a) can’t read or recognise hieroglyphs, b) have an agenda that you seek to confirm (this is called confirmation bias) and, c) know sweet FA about what you are viewing.

The sources Berlant uses however are underwhelming and typical of non-academic writing.

For Egypt he predominantly cites texts and images from obsolete books by E.A.W. Budge. For shamanic mushroom use he cites Gordon Wasson on Siberian and Hindu shamanism and John Allegro on Christianity having been founded on a secret mushroom cult, Jesus being an A. muscaria.

Indirectly, he was also greatly influenced by a book by Andrija Puharich which, I assume to maintain credibility, he is careful not to cite. Rather, his main source appears to have been a paper by Mike Mabry, who himself used Puharich. Berlant basically adopts many of Mabry’s arguments, but changes the mushroom from A. muscaria to P. cubensis.

2. Osiris: Eine Reidentification (2000)

Mike Mabry, a professional photographer, published this puppy in a German broadreach book of folklore about the Amanita muscaria, and he was not alone, as another paper in it by Hartmut Geerken also makes dubious claims about these and ancient Egypt. Actually, dubious is being polite, his citations for archaeological finds of mushrooms are dead ends.

Mabry on the other hand used the Mad Magazine fold-in approach to evidence creation and argued that a classical period lintel from an Egyptian shrine in the Louvre shows proof that the god Osiris was an A. muscaria (when you fold together a photo in a Larousse mythology book).

Apparently, this revelation occurred from him trying to make a face with the wedjat eyes... and then things escalated.

|

| Louvre lintel, with Mabry's proposal. Image Rama at Wikipedia. |

On folding the paper together Mabry concluded that Osiris was actually a mushroom, then he went looking for one that looked like this doctored image, which I have to say it doesn’t. I’d opt for a Boletus myself... or a penis.

He supported this by stating that Osiris is represented in Egyptian art with red upper body and white lower, just like the mushroom (see images above), and that the white crown the god wears is a pin A. muscaria citing the Cannibal Spell from the Pyramid and Coffin texts (Budge 1911, p. 121).

The text:

An updated

translation:

‘and he has acquired the gods’ hearts;

| |

|

Mabry also then includes the red crown as a mushroom, citing the above text and Andrija Puharich who called that royal crown the ‘red plant of life’ in The Sacred Mushroom (p. 26).

To cap this off he argued that the Osirian djed pillar represented the ladder with which one ascends to heaven, but specified that the model for the symbol was a cedar tree, because this was originally made of tree wood and A. muscaria grow under cedars. He doesn’t go full Christmas tree, but the potential is certainly there (pp. 24-5).

|

| Eye of Horus with snakes cited in Mabry. |

He also considers the Eye of Horus to be an A. muscaria because ... wait for it ... that amulet looks like a snake head and the red crown combined ... if you are very selective about your image, and hold it upside down ... because snakes are symbols of mushrooms and their venom supplies a buzz.

Adding that this amulet was fed to Osiris by his son Horus in order to rejuvenate him after death. Wait, but I thought Osiris was the mushroom... (p. 29, citing Budge 1911, p. 89).

|

| Telephone game bullshit that should not occur. None of this is correct. |

This sort of dubious analogy is core stuff for this topic, cannibalistic eating of the Flesh of Gods combined with secret rituals involving kings consuming magic mushrooms. So before moving on, let’s just be clear - the ancient Egyptians had no religious tradition of eating their gods or ritual cannibalism... this is out of date bullshit... even Budge struggled with it in 1904.

‘the fact remains that there is not a particle of evidence in the Egyptian inscriptions.’

Mabry’s

inspiration for his ideas, apart from Mad Magazine, was a book by Martin

Larson (1977) that claimed the Christian Eucharist was derived from an ancient

Egyptian practice of cannibalism, this argument itself derived from the old

meta-narratives that toy with this idea. Also, he dabbles in Robert Graves

(White Goddess) and selected Pyramid Texts as translated by Budge.

3. Mushrooms and Mankind: The Impact of Mushrooms on Human Consciousness and Religion (2000)

James Arthur is a complete blank, as there is no biography available anywhere to flesh out who he is, or was. What I do know is he published this monstrosity with the US based fringe publisher The Book Tree, if you want to read up to date tosh about nephilim giants or aliens building the first civilisations using modified DNA this is the perfect publisher for you.

Arthur’s book is therefore an indulgent exercise in smoodging fringe theory from various sources and making it all about secret shamanic rituals involving the consumption of magic mushrooms in every religious sect from ancient Egypt to Mesopotamia, then onward to Rome and the cult of Mithras, culminating in the Freemasons and western governments who are an elite cabal secretly running the world and imposing fascism on its sheeple.

|

| How many mushrooms? Pectoral of Tutankhamen. Image A. Sinclair. |

Again, like for Mabry (and Berlant), Arthur claimed the A. muscaria was the Food/Flesh of the Gods, the plant of life and consumed in secret rituals of transcendance, but he also added original touches, like these initiatory rites were performed in the ‘multidimensional’ pyramid of Giza with the sarcophagus in the main chamber as decompression unit... ouch.

The ankh, djed pillar and Eye of Horus are again included as symbols of these mushrooms and their secret rituals, but he also includes the was sceptre (ears look like gills), the Aten disk (round and red), scarab beetle, sacred cobra, wings on just about anything (gills), and the tops of pillars in ‘all’ Egyptian temples (Polypores, Pleurotus spec, A. muscaria, P. cubensis).

|

| Scarab from the tomb of Tutankhamen. |

His sources for this book were naturally Budge, Gordon Wasson (Siberian shamanism) and John Allegro (Jesus was an A. muscaria), but for Mesopotamia he used that good ol’ shonky purveyor of Anunnaki woo, Zecharia Sitchin, and then he added magic mushrooms ... did you know Enki was a mushroom? ... I certainly didn’t (pp. 35-8).

For ancient Egypt, Arthur (like everybody else) freely elaborated on ideas that he lifted directly from the following book by Andrija Puharich…

If you think it was weird before, it is about to get weirder.

4. The Sacred Mushroom: Key to the Door of Eternity (1959)

This entire shroomy fiasco began within the 1950s occult scene in New York high society, and in the mind of American parapsychologist and ESP researcher, Henry (Andrija) Puharich. Therefore many, if not most, claims raised in the previous publications are derived from his book.

And it is a fascinating backstory which began when a sculptor named Harry Stone (his surname was actually Stump), for reasons probably only clear to himself (opportunity?), entertained people at a society dinner in New York in June 1954 by handling an ancient Egyptian pendant that was owned by the hostess (p. 8).

On doing this Stone fell into a trance in which he regressed to a past life as an ancient Egyptian priest called RA HO TEP, whom he sort-of claimed was the adopted son of the famous Imhotep of the Old Kingdom. I say ‘sort-of’, because Stone actually just said he was an orphan brought up by a man who made buildings (p. 15) ... later in the transcripts he claimed to be a king...

|

| This

is bollocks, basically just a stream of poorly drawn signs (p. 47). |

The hostess of the aforementioned dinner party was a wealthy philanthropist named Alice Muriel Astor Bouverie (yes, those Astors), who just happened to be a generous sponsor of Puharich and his research foundation, the Round Table. This foundation was dedicated to ESP research, and they dabbled in the notion of an overarching divine authority called ‘The Nine’, which they believed were the Egyptian Ennead gods .... seriously, you couldn’t make this stuff up.

Therefore, she was probably very excited to find another ancient Egyptian medium that evening

in New York, and forthwith sent a written copy of Stone’s trance to Puharich, and then

continued recording these on further occasions, presumably after the sherry,

but before the gentlemen retired to the library.

During these entertaining episodes that were inclusive of automatic writing and speaking in tongues, Stone claimed that a yellow plant with white spots was used by priests to make a cream that was rubbed on the crown of the head. The plant could also be placed on the tongue and was for relieving pain and stimulating psychic abilities.

He also quite conveniently drew this plant for the audience… Yes, that is correct, this guy was an artist.

|

| Stone's drawing of the golden plant, p. 16. |

Later in the

summer of 1955 they tramped out into the foundation’s 65 acre estate

looking for mushrooms that supply a buzz, conveniently guided by instructions

from Astor while she was under hypnosis (p. 78), and on finding

some, experimented with rubbing these on their heads and chewing them (pp.

96-7). The results were unsurprisingly variable, with no significant paranormal activity.

Nonetheless, Puharich continued to document more interviews with Stone, until the latter ceased to produce coherent hieroglyphs (say what?), or go into trances... perhaps the novelty wore off. As a solution he experimented with other receptive people cold-handling Stone’s drawings and documented their visions (see celebrity psychic Peter Hurkos), after which he wrote a book about it, the rest is pseudo history.

These

swashbuckling tales of mystics, mushrooms and New York high society all sound

like firm foundations for a legitimate argument about psychoactive mushroom use in

rituals in far antiquity, no? Well, to be honest Wasson was the

highlight, because once this topic hit Egypt it was downhill all the way.

A few brief explanations of the symbols often used to argue these points on woo sites.

5. Symbols, signs, royal rituals

So here’s the thing with the ancient Egyptians. They were quite good at visual communication. The following images are examples of this and of the importance of understanding context, because your average fringe dweller only looks at the images and ignores the other quite useful information.

These scenes

are not isolated snapshots that are free to interpret, because Egyptian

hieroglyphs were translated nearly 200 years ago. And if someone is prepared to

accept the translation of the name Cleopatra, or Tutankhamen, or Budge’s clunky

and antiquated translations of the Pyramid Texts then they probably have to

accept translation works at a basic level, or they need to start over from

scratch and prove academics wrong...

|

| Forti at Trinfinity blog. |

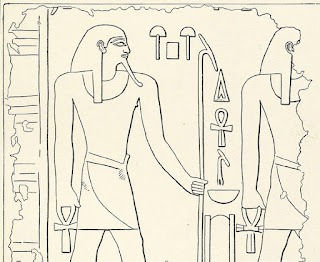

Signs for sunshades

The relief shown above from Trinfinity is often used to argue that the sunshade and its hieroglyph are symbols of the secret mushroom ascension ritual. This is because the uninformed viewer is choosing to see 2 similar ‘mushroom-like’ signs.

Puharich called this sign a sunshade or fan, which is correct, as it represents a feather fan. The name gives this away, because the word shut (šw.t) is most likely derived from shut ‘feather’. Some of the problem here may be attributed to interpreting the English word ‘sunshade’ as a parasol, or umbrella, when a large fan can give shade too.

|

| Left, hieros tomb of Rekhmire. Right, a royal fan from Medinat Habu. |

Nonetheless, the image from Trinfinity does not show mushrooms, it is 3 signs making one word – ‘fan’ or ‘shadow’ (one of the human souls) that was written with the fan sign and the letter ‘t’. The vertical stroke under the ‘t’ has no sound value, it indicates you are looking at a sign group – a word. In Trinfinity's photo these signs are clearly painted different colours.

- It is 3 signs not 2.

- A feather fan is not a mushroom.

|

| Trinfinity again. Image from Pinterest. |

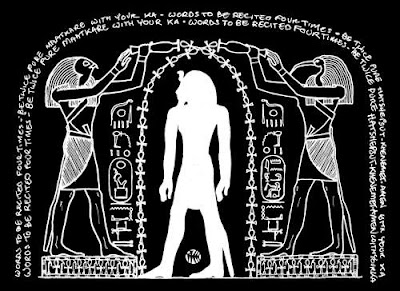

The water of life ritual

This ritual is fairly common from royal monuments after around 2000 BCE. Because of this it is relatively clear to Egyptologists what it involved – it was a symbolic purification libation poured over the king by the gods responsible for granting kingship, usually Horus and Set/Thoth. A variant on this symbolism later also gets adopted by (cashed up) normal people in New Kingdom funerary symbolism.

|

| Hatshepsut being anointed by the gods, Karnak. Image A. Sinclair. |

The ankh was the symbol of life and of regeneration, so at a basic level the image of a king having these poured over him is easy to interpret – the king is granted eternal life. However, the material that was poured over the king is not difficult to fathom, because sometimes they did not use ankhs in these scenes, they used a blue zigzag line, the Egyptian sign for water.

- Water was a symbol of life.

Which makes perfect sense from a culture who were dependent on the annual flooding of the Nile river for their existence.

|

| Trinfinity blog. |

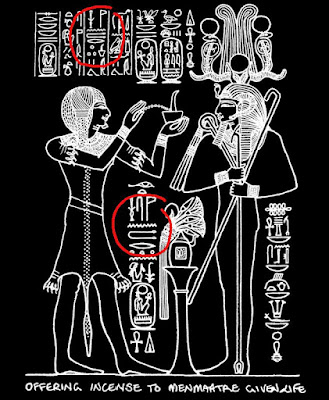

Senetjer offered to a god or king

Again, nothing like being ignorant of ancient symbolism and then claiming on the internet that you have discovered a secret that nobody else on the planet has noticed. This is btw original, as none of the authors cited above have suggested this... 1 point for originality... Forti claims that this scene shows an upside-down mushroom being fed to a god or king.

|

| Abydos temple of Seti I. Image A. Sinclair. |

Now we know that the text and image go together because the sign that identifies the word senetjer is the same symbol as the one that is offered (see cup in top text).

In addition, the word group has 3 signs that look like small balls, which also hints at what it was – little lumps of aromatic resin – like frankincense and myrrh. If you look close you can see the iwnmutef priest is actually throwing little balls into the cup.

|

| The hieroglyph for incense. Sinclair. |

Therefore, senetjer is incense – burning in a cup. The Egyptians burned lumps of incense in small cups with straight sides and thick bases, or on long censors with a hand holding a cup on the end.

These images show the cup with flames rising from the burning resin, which incidentally always points towards the god or dead king who is breathing the sacred smoke.

Also A. muscaria does not have a red stem, but surprisingly fire can be a bit orange-red.

- It is an incense burner.

|

| A. Vase with lotus leaves. B. Temple capital. C. Hieroglyph for chisel. |

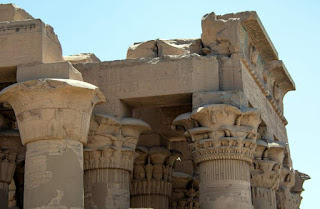

This little theory is again the result of seeing mushrooms where there are none.

But this time the source is pseudoscientist James Arthur (2000) who on visiting Egypt noticed the capitals of temple columns had elaborate plant forms. They do btw... but I am going to emphasise the words ‘plant forms’. This is a long-standing Egyptian tradition and these designs became quite elaborate in the 1st millenium.

Before this the capitals of columns were often decorated with less ornate tops. However, in all periods these decorations were mostly the symbols of a unified Upper and Lower Egypt, the south flower, blue and white lotus, papyrus, or even the heads of the goddess Hathor. None were based on edible or psychoactive fungi varieties, this is subjective thinking.

|

| Papyrus capitals from the temple of Horus and Sobek, at Kom Ombo. |

- Mushrooms are not plants, and incidentally -

- Any and all mushrooms are not evidence for magic mushrooms.

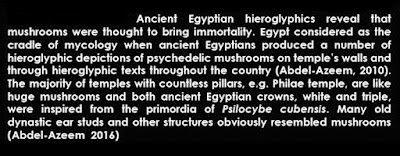

6. Misinformation in media

The text below brings me back to an earlier observation about the unfortunate influence of these publications on media and academia beyond Egyptology, as this quote is not sourced from a pseudoscience website, but rather from the website and papers of a mycologist who has adopted the claims of Arthur and Berlant as though they were legitimate scholarship, presumably with the intention of giving his contemporary research into food production an interesting backstory.

|

| Abdel Azeem et al 2016. |

He is not

alone and a few other academics in mycology, food industry journals and psychoactive research have also made this error, by repeating the various modern falsehoods about mushrooms in ancient Egypt, particularly the myths of the Food of the Gods,

the plant of immortality, gift of Osiris and that consumption of these fungi was the

exclusive right of royalty.

This oversight illustrates the problems associated with sourcing out of date literature when researching a paper, combined with decades long down-the-line citation (telephone game academia), and the pitfalls of combining very specialised knowledge with not consulting experts in other disciplines, because these authors are citing earlier authors in their own fields and not consulting Egyptologists.

Conclusion

I’ll put it as concisely as possible, if you consult an Egyptologist who dabbles in pharmacology they will tell you:

- There is no evidence from pharaonic Egypt for a cultural value for any kind of fungus, except yeast – because bread, wine and beer were really important.

- There is no word in their writing system for a fungus, except possibly yeast, ergot and mould.

- There is no mushroom hieroglyph. The proposals are all misidentifications of existing signs

|

| These are hieros for cool things, but they are not mushrooms. Image A. Sinclair. |

- Nor are there any confirmed images of mushrooms – the misidentifications include lotus leaves and flowers, papyrus, and sundry cult symbols.

- There have been no findings of archaeological residues of any mushroom from Egyptian burials or food preparation areas... nada.

- Neither P. cubensis nor A. muscaria are known from Egypt, so the choice of these by pseudos is an example of ethnocentrism - ‘our drugs must be their drugs’. A. muscaria is a cool climate mushroom that grows in oak and fir forests, the yellow variety (var. guessowii) is specific to North America. P. cubensis is a tropical fungus that grows in dung in warm wet climates, it is the most well-known psychoactive mushroom outside of European folklore about A. muscaria (see Guzman et al 1998). If the Egyptians did have a local psychoactive mushroom it is unlikely to be these.

Symbolism - The symbolism of ancient Egypt was not photographic, they showed the important information, which means they depicted objects from various angles in one image. Therefore, it is quite important to know their symbolic vocabulary before jumping to conclusions from a blurry photo on the internet. Being able to read their texts does not hurt either. The images used by pseudos to support their arguments illustrate their lack of insight, they are subjective, ignore the study of hieroglyphs, they ignore colour (unless it suits their argument, oh look, it’s red).

Values - The Egyptians lived in another time, they therefore placed magical value on things in their environment that we might consider mundane, if we ignore this we are in danger of imposing our values on them, like believing that a bunch of onions or bread or water must be a magic mushroom, rather than something of local significance. However, the Egyptians did value certain psychoactive substances, we know they did, like alcohol, lettuce, the lotuses, mandrake, these had spiritual, medicinal and recreational value.

Sources - These are not always made clear, particularly when an author is trying to give their claims a veneer of credibility, like Berlant, who is careful to avoid citing Puharich, yet who is indebted to The Sacred Mushroom through Mabry. I would say the same for the academic publications that cite mycology and ethnopharmacological texts going back 50 years. Like the myth of mushrooms being exclusive to kings or the Food of the Gods in ancient Egypt, but now this nonsense is on every perky website devoted to edible mushrooms on the planet.

Close

As you may have noticed the claims about magic mushrooms in ancient Egypt are a veritable trip down the burrow of that anxious white rabbit from Alice’s Adventures with obligatory hookah pipe, giant mushroom, add a judicious dash of paranoia, then a teaspoon of past life regression and a pinch of automatic writing for lols. To be honest the amount of artistic licence in this myth is actually mind boggling.

That being said, while entertaining at many levels, this narrative does not provide any evidence that the pharaonic Egyptians knew mushrooms, ate them, or even valued them in any spiritual way.

It is all poorly argued speculation.

Andrea Sinclair

2022

|

| Drawing by Harry Stone, don’t laugh, they were serious, Puharich p. 111. |

Don’t do it, it’s a trick (out of date)

|

| Drawing by Peter Hurkos after handling Stone's drawing above, Puh. p. 112. |

Mycology

Academic citations of the myths (sample)

|

| I just like A. muscaria. Taken in late autumn A. Sinclair |

Pseudo sources

Allegro, JM. 1970. The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. Sphere Books.

Arthur, J. 2000. Mushrooms and Mankind: The Impact of Mushrooms on Human Consciousness. California: The Book Tree.

Berlant, SR. 1999. ‘The Prehistoric Practice of Personifying Mushrooms.’ Journal of Prehistoric Religion 13: 22-30.

Berlant, SR. 2005. ‘Entheomycological Origins of the Egyptian Royal Crowns and the Esoteric Underpinings of Egyptian Religion.’ Journal of Ethnopharmacology 102: 275-88.

Berlant, SR. 2019. ‘Introduction to the Mycolatrical Origin of Egyptian Religion: Why Identifying the many Mushroom-like Objects in Egyptian Art as Mushrooms can Explain those Objects and Ancient Egyptian Religion far better than Egyptologists have. Draft – Academia.edu/Researchgate.

Berlant, SR. 2019. ‘An Egyptian Christmas Tree in the Tomb of Roy. Draft – Academia.edu & Researchgate.

Bernstein, M. 1956. The Search for Bridey Murphy. Doubleday. (First published in 1954 in the Denver Post).

Forti KJ. 2018. ‘Sacred Mushroom Rites and the

Hidden Meaning of the Egyptian Ankh.’ Trinfinity blog.

https://trinfinity8.com/tag/amanita-muscaria/

Geerken, H. 2000. ‘Paramykologie.’ In Der Fliegenpilz: Traumkult, Märchenzauber, Mythenrausch, W. Bauer (ed), 23-30. AT Verlag.

Lloyd, E. 2016. ‘Mysterious Ancient Mushrooms in Myths and Legends: Sacred, Feared and Worshiped among Ancient Civilizations.’ Ancient Pages.

https://www.ancientpages.com/2016/09/14/mysterious-ancient-mushrooms-in-myths-and-legends-sacred-feared-and-worshiped-among-ancient-civilizations-2/

Mabry, M. 2000. ‘Osiris: Eine Reidentifikation.’

In Der Fliegenpilz: Traumkult, Märchenzauber, Mythenrausch, W. Bauer

(ed), 23-30. AT Verlag, 23-30.

Puharich, A. 1959. The Sacred Mushroom: Key to the Door of Eternity. Doubleday.